GRAPHIC NOVELS

SCRIPT WRITING

THE WRITER’S DESK © Chad Corrie

We have been looking at graphic novels and will continue to do so in this short series of essays, focusing on the nature of how to create them should you wish to do so for yourself or just be interested in the process in general. In the previous essay we were talking about the basic concept of figuring out just how large your work would be and where (what format) it would work/fit best. I trust you’ve been able to get that matter settled as we move ahead into the first stage of getting your story underway, that is writing the script.

Two Different Scripting Methods

You’ll find that there is no right or wrong way to write a comic or graphic novel script, only various preferences for certain publishers, artists, and writers. Outside of these there isn’t a set-in-stone rule for how to go about crafting your script, but there are two differing ways on how to approach the matter. One is called plot first or Marvel scripting and the other is called full script.

Back in the early days of Marvel Comics the editor of the company, Stan Lee, who was also their writer on many books, found that he couldn’t run the company and do the writing at the same time if he wanted to do a good job. So he adopted a unique approach to writing his tales. This involved having the artist for a book come into his office where he would tell them the story for the book in the form of its plot. He’d pass on the plot for the book and then leave the artist to go draw it. When the artist came back with the finished pages Stan would go in and add the dialogue and finish telling or re-designing (since some artists sort of added and changed things along the way) the story. The result was something of a hybrid creative process that relied more on the plot being a guideline for the art, which really told the story and was fine tuned with the dialogue and any other points of story crafting.

This is not the common or preferred method of creating graphic novels, but it does have some fine points that work well for people who are both writing and illustrating their own work. The main reason why publishers aren’t too wild about the idea is that it places a lot of power in the hands of the artist and if you know anything about the modern comic/graphic novel industry it is that artists aren’t always the most timely or reliable in certain areas. Having them be in charge of basically creating the entire book—sight unseen in most cases—is a bit dicey to publishers who have deadlines and wish to see a product done on the story side so they know what they are getting involved with before they move ahead (as well as put money upfront).

This method of storytelling is not that favored by many writers either who wish to have the full version of their vision expressed on the page. They wish to have something that is finished and set in place, something they can have control over in a basic sense of the word. And this is why many look to use what is called a full script method for their scripts. As the name implies full scripts are the entire script—filled with the page breakdowns, dialogue, and so forth. Everything is expressed or explained leaving little ambiguity.

Full scripts are the preferred means of writing when it comes to publishers for in them they have control again and don’t have to put their story (and money) in the hands of an artist who might not meet deadline. They can have the option of keeping it on track by reassigning it and/or adding in another artist to help out. It also is a boon in that they have the complete story in their possession and they can better prepare in finding ways to promote it as well as edit and tweak things before they start spending the time and money in working with the rest of the creative team to start creating the story.

No matter what method you adopt for your script you will still be dealing with the same four basic components, that is: panels, dialogue, captions, and sound effects.

Panels

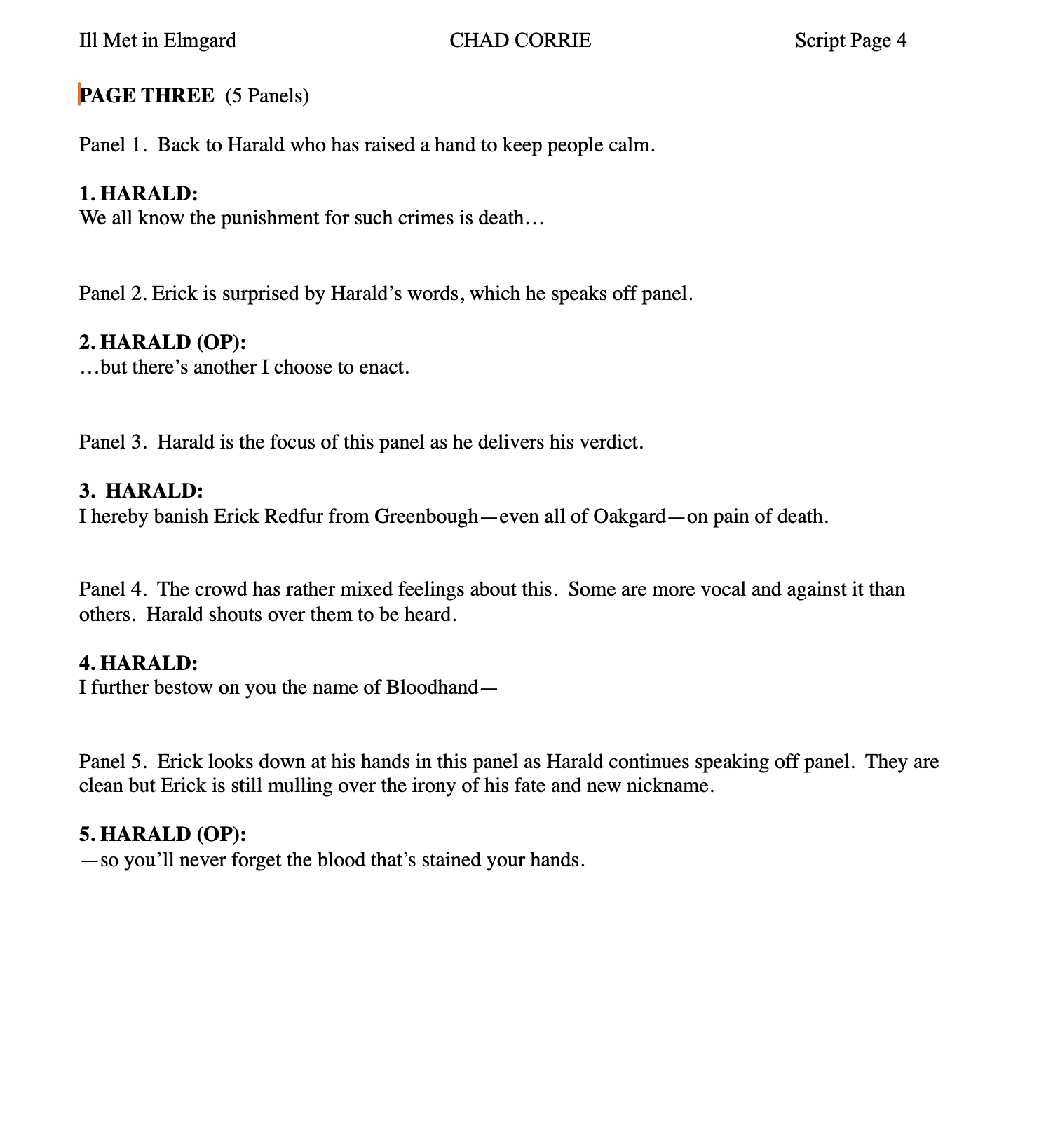

Panels are like freeze frame bits of the action that show something happening in the story. Each is divided by a gutter, a strip of space, that separates one panel from the others so to help the reader know what is part of the action at any given time. Panels can be of any size and shape but tend to often resemble squares and rectangles.

You are free to put any number of panels on a page but keep in mind that the more you add the smaller they will be and if you have a lot of dialogue or action going on it might get lost or dominate the scene if the panels get too small.

In most cases you’ll find that modern comics tend to have about five to six panels per page. Some will go with three or four and even branch off into seven or eight but most will tend to hover around the five or six per page mark. You can also have one large panel—basically being the whole page—or even a two page spread being a single panel as well, but these aren’t the norm. Often these larger panel set ups are for large battle scenes or something that is better viewed in a panoramic set up for story related issues. You don’t want to overdue this type of set up in a book either as it will diminish the impact they can have on the story and reader.

Dialogue

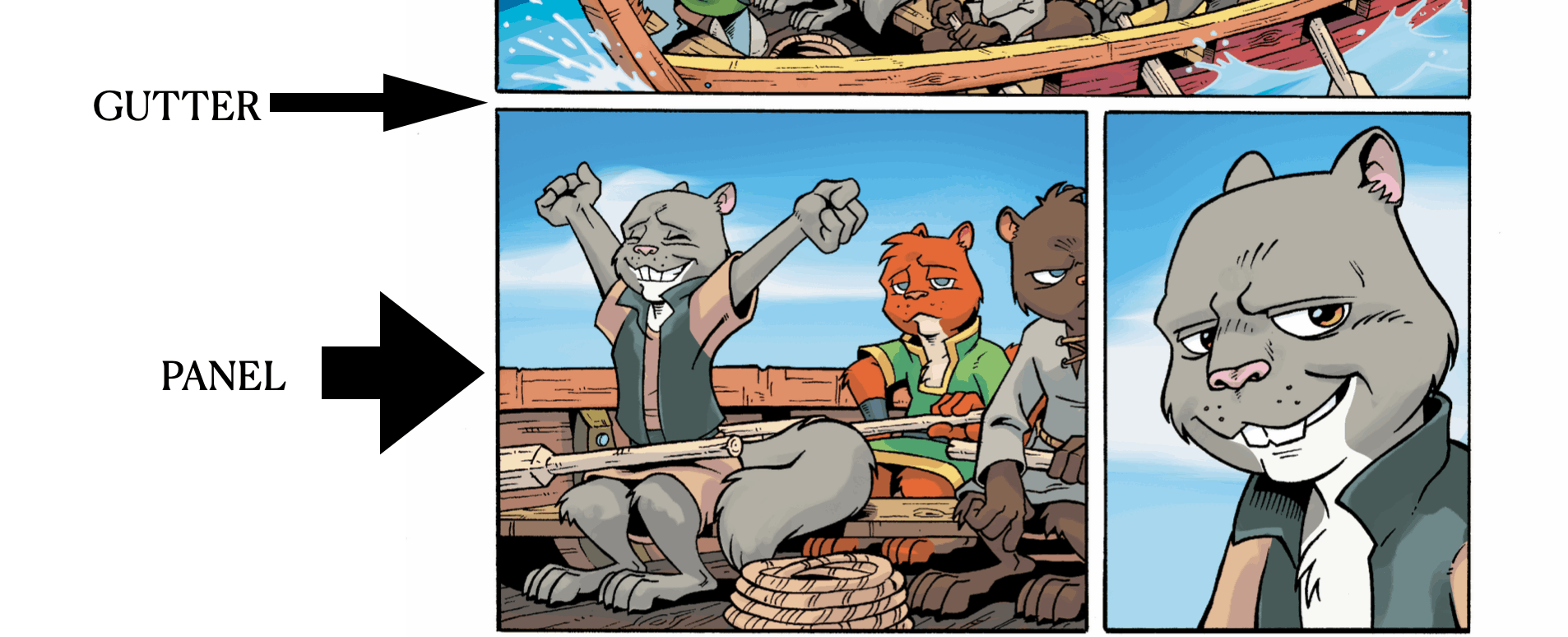

Dialogue, captions, and sound effects all fall into the category of word balloons to some degree. These are the means by which story in the form of exposition, speaking, and character narration complete the image on the page. Captions are more or less boxes that can be used to relate time and place, used for narration, or are put into use in the place of thought balloons—that is a bubble that is used to show what a character is thinking. Many modern comics have opted to use the caption in place of the thought balloon for various reasons but you can still find the thought balloon in publications, these being in younger aged markets and newspaper comic strips in most cases.

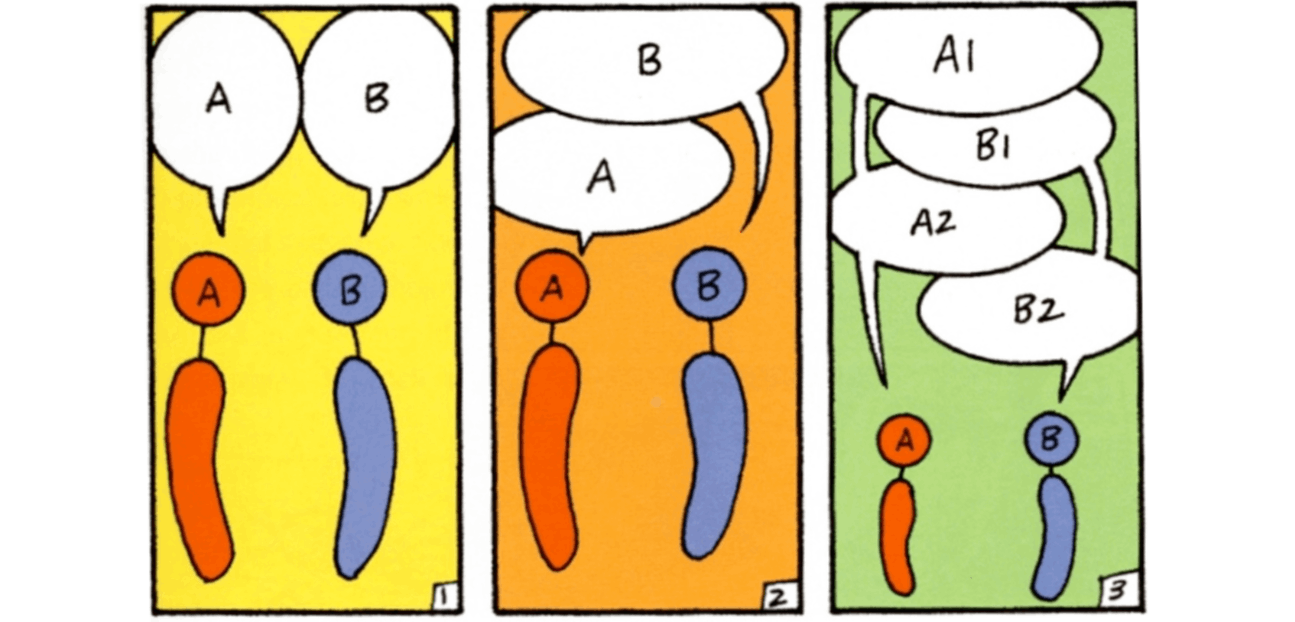

Dialogue can be a challenging thing when you first start out, even posing some challenges to veterans in the field from time-to-time. First, let’s talk about what dialogue is. Simply put it is a conversation or means of vocalization for any person or thing that is able to express itself in words, grunts, etc. Dialogue is often placed inside what are called word balloons, these are simple oval shapes that have tails which point to the speaker. Word balloons can be drawn to show various types of communication such as: whisper (dashed lines are used around the word balloon instead of a solid line), the voice is coming from an electronic device (word balloon is jagged edged), you hear a voice but don’t know what where it is coming from (word balloon with no tail), and so forth. Word balloons, like panels, are read top to bottom left to right in Western comics.

The big challenge that someone starting out often falls into is that they write too much to fit into a balloon and/or even page. Like writing a greeting card, you have to learn how to say a lot with a little. This means using contractions over multiple words (unless a character is more proper in their speaking) and look at getting things simple in their expression.

This again is an overview of the concept. You might be able to write longer snippets of text in your word balloons for your story based on what sort of genre you’re doing and/or what you’re working on in general. When in doubt look at some other comics and graphic novels out there in the libraries and store shelves and see how they do things. The important thing to not forget in all this is that dialogue, that is to say language, is a powerful tool to help define your characters. So don’t miss your chance to really hone in and flesh out what you can so the art compliments what you’re able to convey in the text.

Sound Effects

Sound effects can be an interesting thing to tackle in your scripts as well. Some avoid them all together and then there are others that overload their script with them to the point of having them become distractions. When going about using them it is better, I think, to put them in if they add something to the story. Graphic novels aren’t movies. They have limits. You don’t have soundtracks going on in the background nor a cacophony of foley artists working their magic to punch up the tale. Instead you have only the art and the text to share your story…and a limited amount of space in each panel to do so.

So before you opt to use a sound effect stop and think if it would add something to the story. Do you really need to have the sound of those tommy guns going off when we can see them in the panel? Is the explosion on the panel made better with the big “KA-boom” you want to add into the works? Sometimes you may want to use them to help “brand” a sound for a certain weapon or action. This might be the sound of a certain ray gun you invented for your story, what the dimensional rift opening and closing sounds like, or even a superhero using one of their powers or gadgets. Sound could also be an element of the story—the characters having to listen for it or marking a villain or event in a special way—but in however you use sound effects I would advise being judicious.

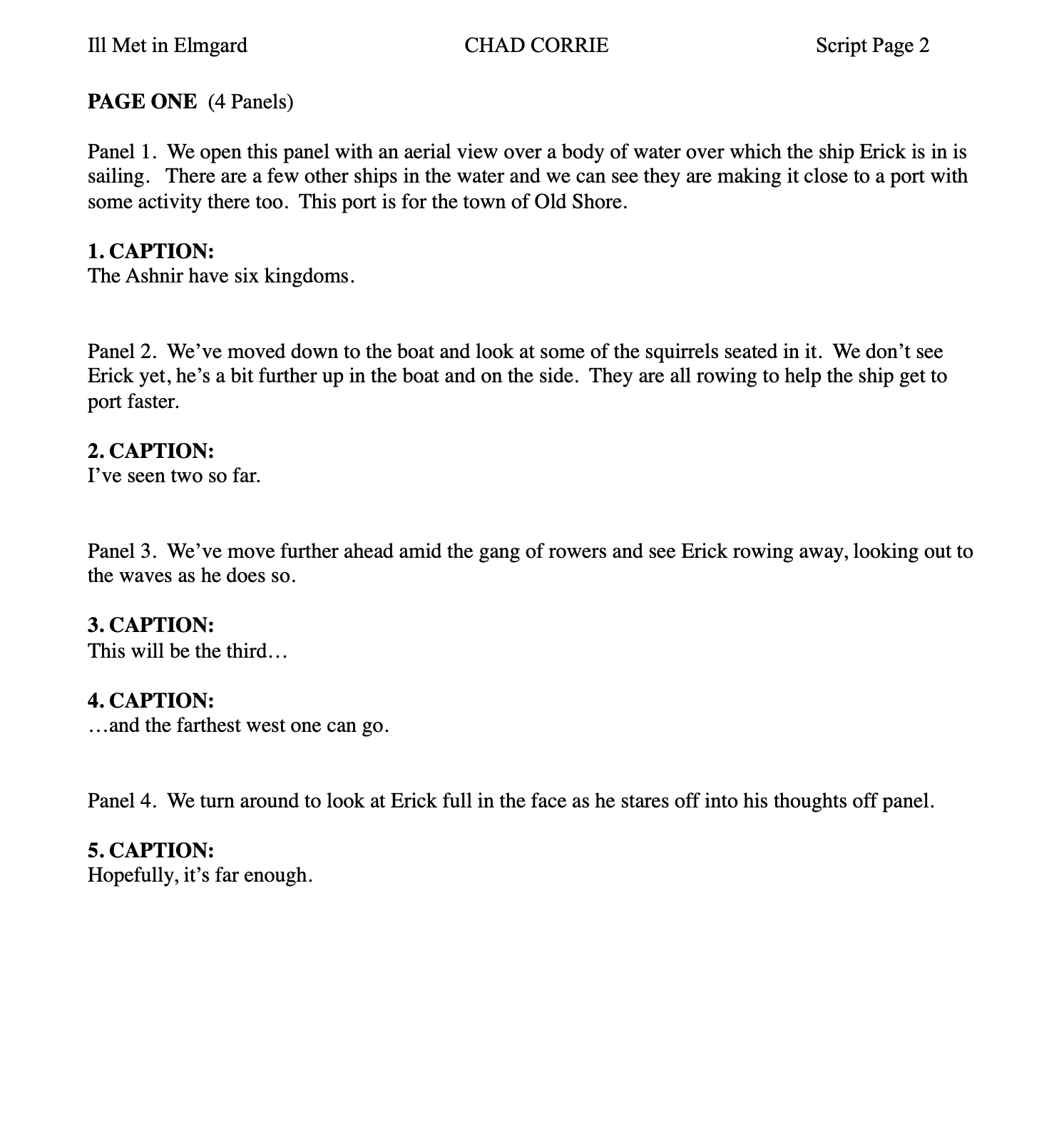

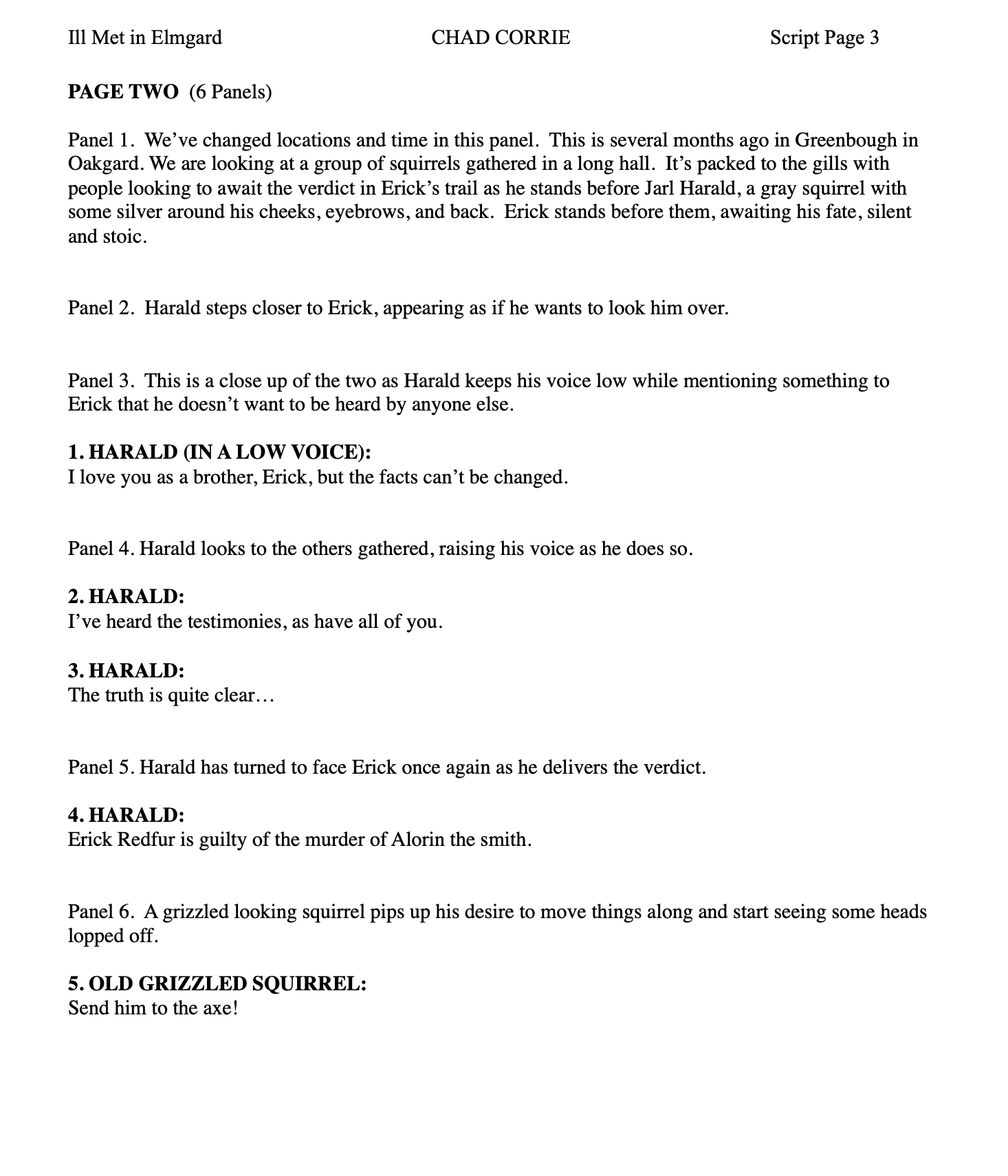

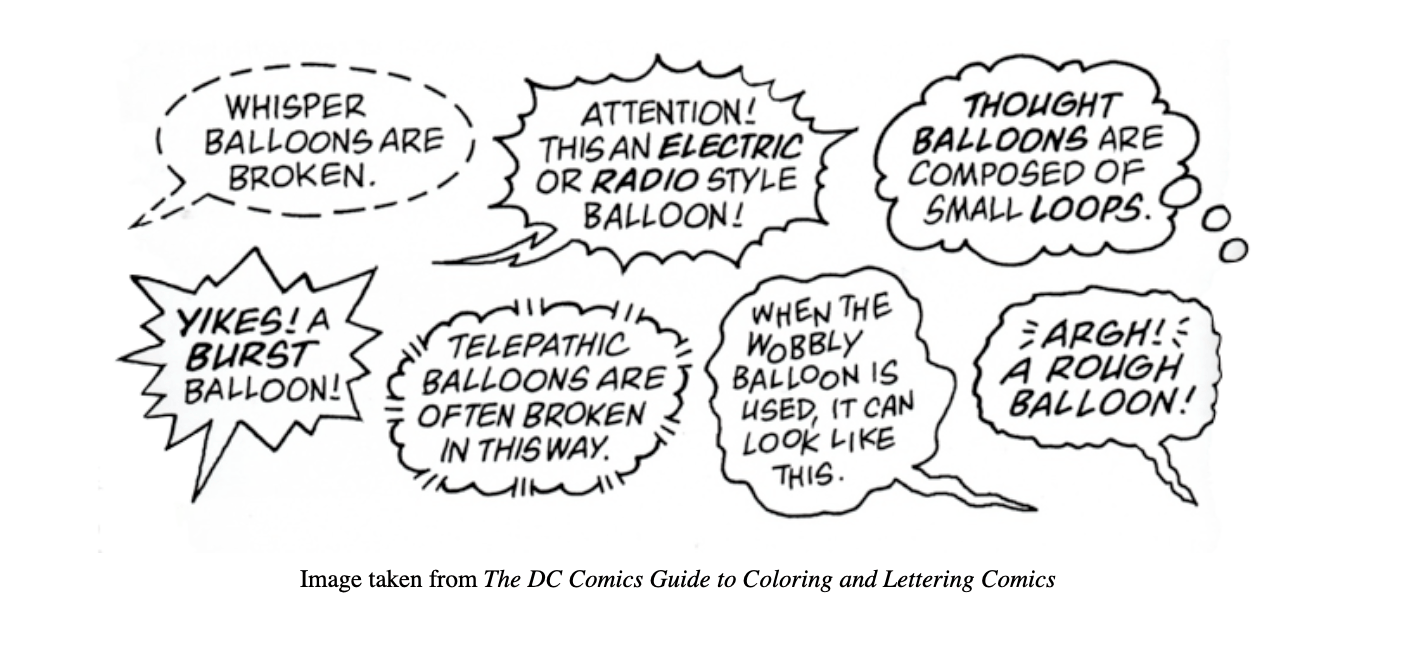

Below I've included a few sample pages from a script I’ve written to provide a working idea of how to put together your own script formatting (click to enlarge). Please note these script pages are © Chad Corrie all rights reserved. And no use of them outside of personal study or use, should be made without my written consent.